11/11/02

11/11/02

Knickknacks, Souvenirs, and Bylines

A common writing exercise for those who are just beginning to learn to string together ideas and images in such a way as to merit a byline is to take an interesting object and imagine a story behind it. Although I doubt that it is directly a result of such exercises, many writers become knickknack collectors. Not only do stone elephant bookends, for example, offer up stories, both anecdotal and fictional, but they also may be held, observed, and described.

The elephant bookends, with four etched lines like fossilized spider's legs across each ear, seemed lashed to the novels by the webs that stuck to the spines of both the stone animals and the books. Through the dust, he saw that the last book on the top shelf was As I Lay Dying. Faulkner always raised memories of his youth.

Knickknacks or not, all writers are collectors. Each has stored away images and impressions, reactions and reasons — feel. We draw on them when they apply to our work, taking liberty to remold the scene or the circumstances as necessary, turning them over to see the cast of the light, running memory’s fingertips over the texture of the room. The emotion that permeates our vision of any given scene from life is another shade of import.

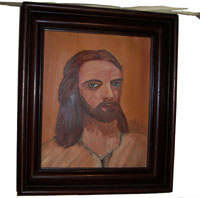

For example, whenever I think of paintings with eyes that follow the viewer, I find myself at the top of my maternal grandparents’ stairs, in the second-floor hallway. With young fingers dug into the shaggy golden carpet of the steep stairs (easier to climb than to stride), I would look up and see the eyes of a portrait of Jesus following me. I was always aware of that painting, when I walked — ran — from room to room. I had no defined beliefs, then, so I do not know whether it was ghosts or God that I imagined peering at me through the canvas; I just felt watched.

The painting had been done by my grandmother, and it was the central object in the house that I associated with her. My only memory of my mother’s mother is a flight of stairs away from her. She was sick, and I didn’t understand that it was not an illness that I could catch. I stood at the bottom of the shadow-draped steps, the Jesus painting out of view around a bend, and my grandmother across the hall from it, in bed, dying.

Of course, grandparents’ houses are filled with intriguing items and memories and stories. The world changes over the generations, and our closets and attics archive the change for rummaging children. During a visit this past weekend, my parents delivered, on behalf of my paternal grandparents, two watch fobs that once belonged to my father’s great grandfather. I had to look up the word “fob.” One of the two is a gold-capped piece of staurolite, a mineral that can form naturally in the shape of a cross. Such rocks are also known as St. Andrew’s crosses or fairy crosses, and it is not surprising that they’ve lore about them.

So there are the curiosities that hint of magic. The old books and the canes. The mantle clock that bonged too loudly for its size on the cabinet with medieval knights carved into it (which came with the story that the person from whom my father’s mother purchased the piece of furniture didn’t know what he was selling and vastly undercharged, a mistake that his superior tried in vain to remedy).

There are the remnants of history. The Wild West six shooter and the strange chunk of metal and wood that seemed as if it must have been among the first attempts at pistol making. The old records, as fragile as glass (and broken as easily by careless grandchildren). The dishes shielded within display cabinets, and the assorted jewelry. There are the items that survived actual usage and everyday life. The pen on which a bather lost her suit when it was turned to write. The old magazines. The big yellow metal sled tucked in a storage space. The toys of parents who were once children.

And there are the pictures. On this Veteran’s Day, I recall the pictures of my grandfathers in uniform. I think of all those photographs that led me to believe, once, that in the years before the 1960s the world had existed in black-and-white. (“Grandma, how did it feel to become color?”) When I was young, only the style — the outfits and the hair — seemed different across the years of the past; everybody remained in their relative categories of older-than-me. For previous generations, the pictures and paintings of their grandparents and great grandparents must have made their times seem rigid and posed. That may be the greatest benefit of improved photography: the ability to see our relatives as they were, candidly.

As the writer’s imagination grows, writing becomes a bit like meditation. As the person comes across the perennial experiences of life, he can better place himself in the position of others. The soldier looking at an odd contraption — that ancient gun — new and bizarre to him as it is old and bizarre to his distant progeny. The husband-to-be preparing for a wedding. The wife framing a sketch of the Brooklyn Bridge after a trip into New York City. The daughter learning to play an instrument. The sister reading notes in her high school yearbook. The son writing a story. The mother blending the flesh tones with her brush to express adoration for the Son of God.

In the midst of a contentious estate battle with my grandfather’s second wife, my mother asked me if there was anything that I wanted from the house. I asked for the painting. Had it been among the inventory (a cold word) that had mysteriously gone missing, I might have done something rash — in my likely futile wordsmithy way. But now, here it hangs, at the top of my stairs, and one detail stands out more than the eyes, which frighten me no longer:

Mary Rancourt Potter — ’63

11/04/02 Voting: Finally Becoming an Urgent Cause (Government)

10/28/02 Freedom to Mourn; Freedom to Be Warned (Religion)

10/21/02 The Writer’s Autumn Leaves (Life)

10/14/02 Seasoning the Balance (Life)

10/07/02 Fundamentalism by Any Other Name (Religion)

Archives back to 10/29/01